How we manage soil landscapes is crucial to resilience

The Guardian, 16 December 2022

Three experts on why soil hydration matters in combating the long-term impact of droughts and floods.

Australia faces worsening extreme weather events, says the 2022 State of the Climate report, published by the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO. Using soil rehydration and regeneration to build resilience in our landscapes could be vital, experts say.

“Extreme climatic events, including both flooding and extended drought, are becoming the new norm,” says Dr Chris Pratt, a soil geoscientist at Griffith University. “Consequently, managing soil landscapes in preparation for these conditions is of crucial importance.

“While the current pattern of higher-than-average rainfall over much of Australia might seem to ease concerns regarding soil rehydration, it actually highlights a broader looming challenge.”

Why hydration is important

Rehydration has the potential to regenerate soil health, Pratt says.

“When we have extreme weather events, like floods, the soil structure is very susceptible,” he says. “In the [February 2022] Lockyer Valley flood [in south-east Queensland], about 30% of topsoil was lost into the bay because of poor soil structure.

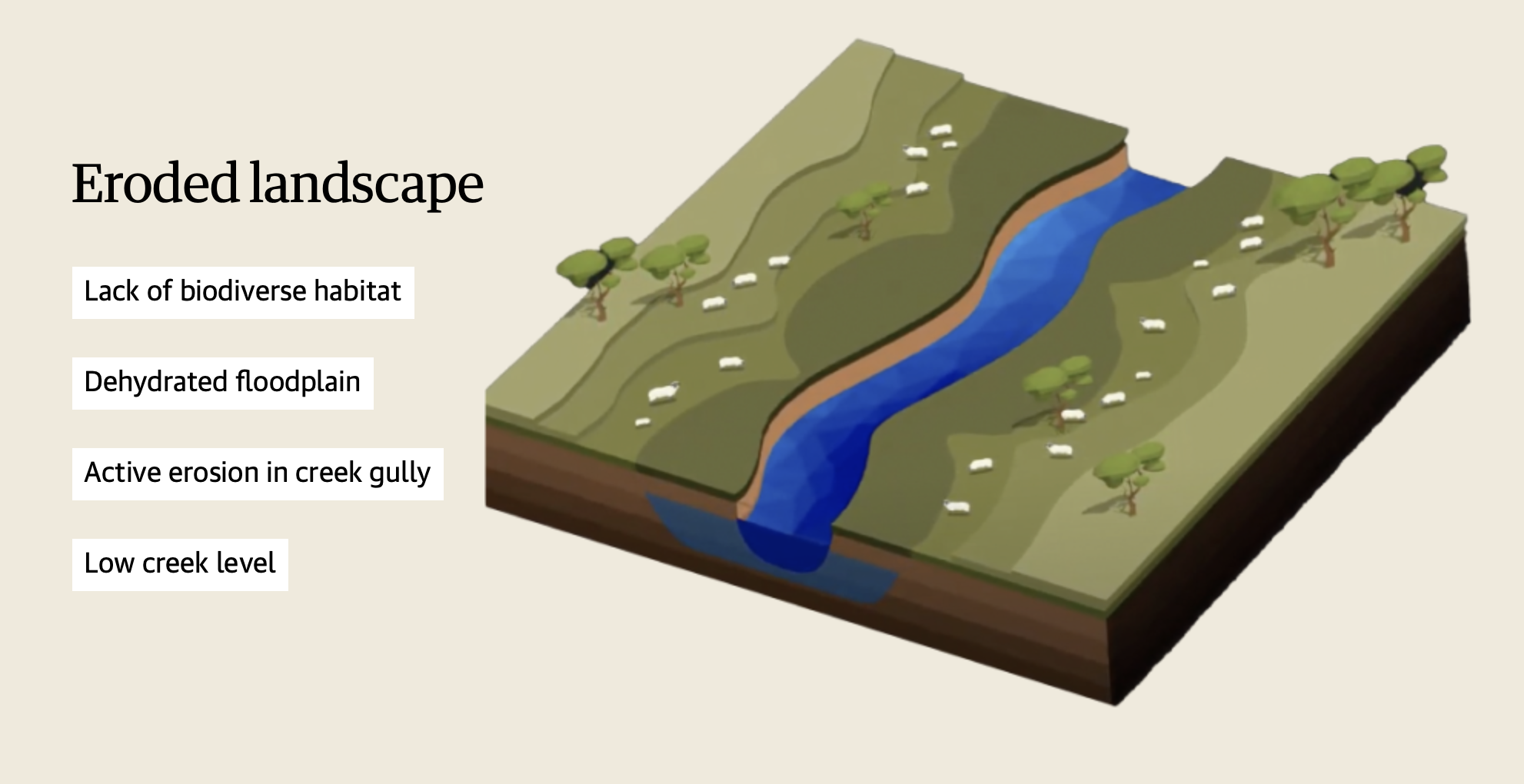

“Water insulates landscapes against use, and soil is a good medium for holding onto water. If we degrade soils and deforest our landscapes, the country is physically incapable of behaving normally, soil loses its physical structure, and is more prone to erosion.”

Professor Justin Borevitz, who studies landscape regeneration at the Australian National University’s Research School of Biology, agrees.

“In the height of drought, or when preparing for drought, post-floods, we need to ask: how are we going to keep water in the landscape, slow the flow and make it available for plant roots?” he says.

Through good land management practices, landholders and managers across a catchment can make changes that stop landscapes degrading and improve soil health, Borevitz says.

“In a landscape where you get droughts and floods, land clearing and overgrazing, the country can’t recover quickly from weather extremes. Australia’s soils are very sensitive to weather effects.”

Image credit: Grow Love Project

How natural hydration works

When rain falls onto a soil surface, whether it soaks in or runs off is largely due to topography – the forms and features of the land. Biodiverse vegetation can slow the water flow and enable surface water to soak into the ground, into the deep layers of the soil, and often into aquifers to become part of the water table.

“Hydrologically, the water tables that are 50 metres below the surface take more than a year to fill,” Borevitz says. “Slowing and holding water enables it to flow down into the recharge zone, rehydrating the landscape for groundwater recharge, and becoming a water bank for future years.”

That water bank is available for plants and essential microorganisms in the root zone. Through transpiration, plants such as grasses, shrubs and trees then release moisture into the atmosphere from their stems and leaves, enabling the plants to dissipate heat in direct sunlight, and cool through evaporation.

Landscape rehydration methods seeing results

When earthworks are used to build depressions in the landscape to slow the flow of surface water during and after rain, this enables water to pool and rehydrate the landscape.

The Mulloon Institute’s principal landscape planner, Peter Hazell, says these changes also create cooler landscapes.

“One of the key reasons our landscapes have become so degraded is the loss of soil organic matter, the sponge layer,” he says. “Soil that contains organic matter in the top 30cm can hold four times its weight in water.

Photograph: Mulloon Institute

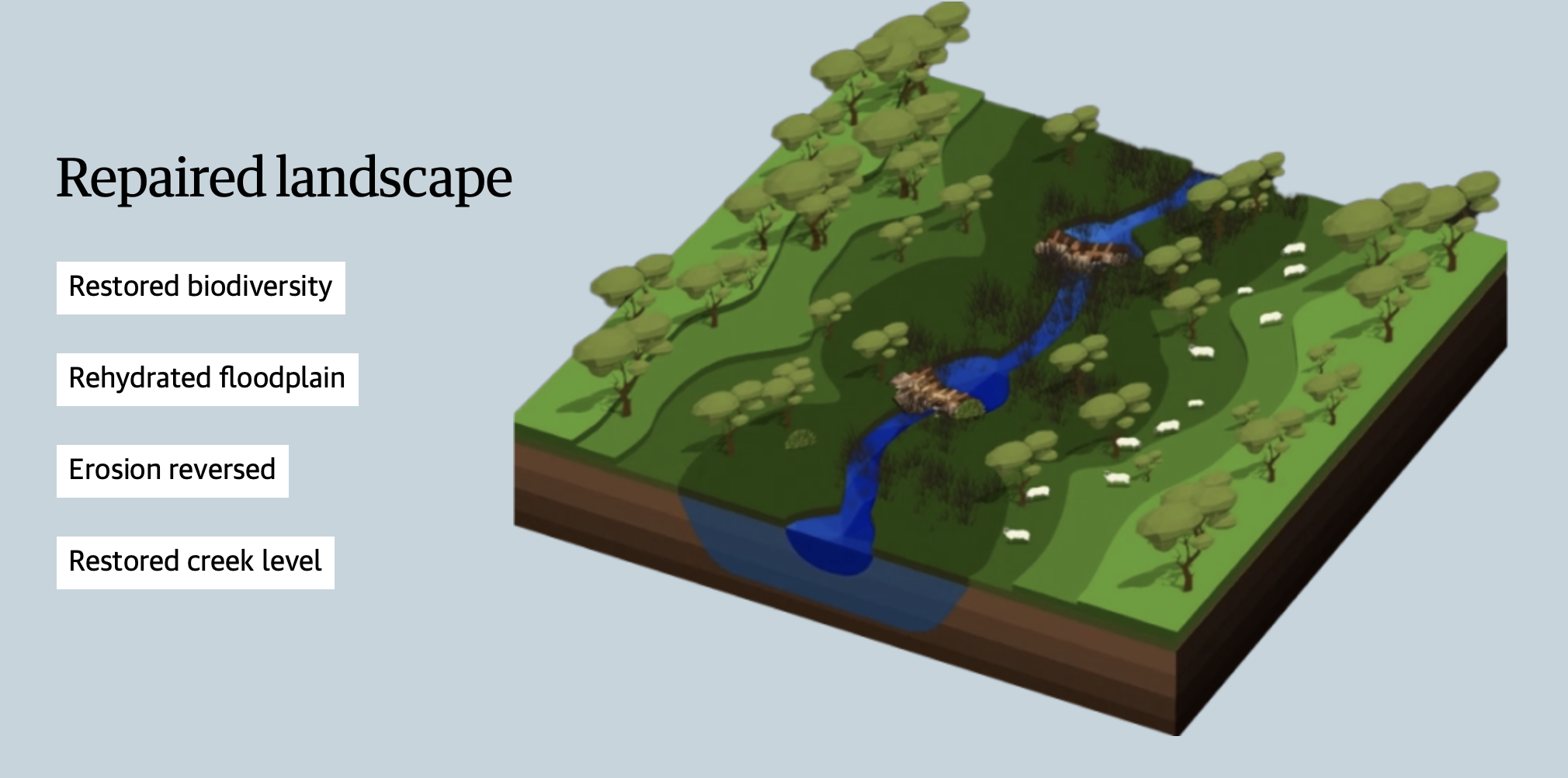

“We’ve identified that landscapes that are hydrated, and with no gully erosion, or where gully erosion has been reversed, are the greenest and coolest country in the hot months.”

Collaborative partnerships between the business sector and philanthropic and research institutes can create solutions to the challenge of hydrating the landscape and building resilience to the future impacts of both droughts and floods.

The Mulloon Institute’s projects focus on initiatives that rehydrate by slowing the flow of surface water, allowing water to be collected by the landscape and improve soil health. With funding, these projects are beginning to make a difference.

Vitasoy Australia chose to get behind the institute and has pledged $1.25m. It has a vested interest, since it aims to source its raw materials from Australian farmers, rather than import them. David Tyack, the managing director of Vitasoy Australia Products, says: “We believe in supporting Aussie farmers and actively pursue an Australian-first sourcing policy, meaning that if we can source our raw ingredients from Australian farmers, we always do.”

Initially, the institute’s rehydration project* was focused solely on the Mulloon Creek catchment, where landscape planners designed and installed leaky weirs, to slow the flow of surface water and return the creek to its natural state – a series of linked billabongs. Natural and planted revegetation has created a more healthy and biodiverse landscape.

More recently Hazell has been using satellite imagery to create 3D models to identify how water moves through the landscape and creates patterns of erosion in other New South Wales and Queensland catchments. Collaborating landowners are learning how to re-establish natural flow patterns on flood plains by using rocks and vegetation to create choke points and slow water, reducing soil erosion, Hazell says.

* The Mulloon Rehydration Initiative is jointly funded through the Mulloon Institute and the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program, with assistance from the NSW Government’s Environmental Trust.